By André Gakwaya;

Patrick “Kadhafi” Mwenedata was born on May 17, 1982. His father Marcel Sizeri, baker, is a survivor of the Tutsi genocide in Rwanda, while his mother Esperance Musasanzobe and his younger brother were killed in front of his eyes, in front of the Kibagabaga Catholic Church. He gives us his testimony:

“We used to live (and still live) near the current Kimironko sector office. At the time, we were administratively dependent on the old Remera sector and the old Kimironko cell. I started my primary school at Kibagabaga Protestant School, but in 1994 I was enrolled in 5th grade at Remera Primary School, now called Saint Paul International School.

I already knew the distinction between Hutu and Tutsi since at school, Tutsi and Hutu children had to take turns getting up. I also knew what the Interahamwe militiamen were capable of. And then, during political demonstrations, we heard their slogans “We are going to exterminate them”. Sometimes some classmates would tell us that when the time came, we would be exterminated, we cockroaches that we were. We were used to this kind of talk that terrified us, but we hoped that one day this hateful atmosphere would end.

On the evening of April 6, we were with the family when President Juvénal Habyarimana’s plane was shot down. We spent the night at home, but the next day things had changed. The radio was playing classical music and no one was allowed to leave his home. Granted, I was still young, but I asked what happened. I was told that the presidential plane had crashed and that President Habyarimana was dead.

At that time, gunfire was heard coming from Kanombe towards the CND (Parliament) area. We stayed at home and our parents looked scared. We lived a little higher than our grandfather’s house. Papa’s little brother also had a house nearby. We had good relations with our other neighbors. Dad and the other adults began to exchange opinions on what was going on. Around 9 or 10 a.m., our household employee wanted to go to the main road, but he returned quickly saying that things were getting worse and that a certain Jean-Pierre Nzaramba, a Tutsi, had just been killed. People started to get scared and went back to their homes. We stayed there until 1 p.m. The people who lived at the “Groupement” [crossing of the main streets of Kibagabaga and Kimironko] and towards the BK [Bank of Kigali] fled and passed in front of our house saying: “Flee, flee! What is happening is serious! ”. They were being pursued by the Interahamwe. But we stayed inside our house with the doors closed. Our domestic worker went out to see what was going on. The militiamen stopped their course to rush into the house of a certain Bucyana, breaking down the doors. Dad then told us to get out of the house because after we went to Bucyana’s house, they were in danger of going after us. At the bottom of our house, there was a house under construction, which still had doors. We walked in with Mum, while Dad stayed outside to see what was going on. Afterwards, he went up to grandfather and my uncle.

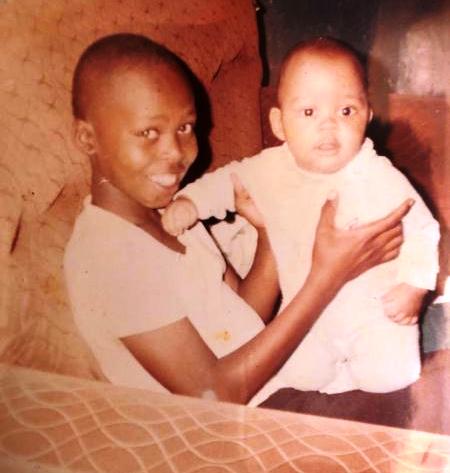

In 1996, when young Patrick was 13 is holding a baby boy from his father’s second marriage after the genocide against the Tutsi.

“The next morning, we learned that neighboring families had been killed”

We spent the night in the house under construction. The next morning we learned that neighboring families had been killed, so we had to flee. We went down to Kimironko, to the ADEPR church which was called “at Mpambara’s”, because Mpambara was in charge of this church. We found other families there who had taken refuge there and we stayed there for three days. On the third day, in Karama, where there were other refugees, the Interahamwe launched an attack. It was April 10th. The militiamen killed people and among those who were able to survive, some arrived at Mpambara’s house. We were children, but we understood because adults were more and more overcome by fear. In the evening, the militiamen attacked us. We were inside the church, they asked us why we were here and that those who had money give it to them if they wanted to save their lives. They took the money and walked out saying they were forgiving us. But in the morning, it was found that all the same three people, Sylvestre Niyomubisha and two other neighbors, had been killed: their bodies were lying in front of the church.

When the adult men saw this, they made the decision to leave, thinking that the militia would come back. They came back to our place. But our Mother and we, her children, went to hide with our co-religionists, a family who had come to pray with us during our stay at the ADEPR church. They first suggested that Mom hide me in their house. It was April 11. Finally, my father convinced them to also take my mother, the youngest and my sister. We parted ways with Dad. In this family with which we were going to spend a few days, there was Vestine, a young girl who still lived with her mother (the father had died) and her brothers. They were Hutus, they weren’t being hunted down. On the other side, my grandparents, my aunts, they were a whole group with other neighbors. They left the church and went back to the neighborhood. They all hid in the same place, with a Tutsi named Silas and they were denounced by their neighbors. It is estimated that around 60 people were killed in the April 11 massacre. Many children were not killed that day except two. It was fellow believers who came to visit us at the young girl’s house who told us everything. We were in hiding very close to this place. Other people who used to pray with us were killed in the carnage.

Five days later, we were still in the same family, at Vestine’s, and his brothers ordered him to drive us out. We could not return home, because our houses had been looted and destroyed, our families exterminated… We took roundabout paths, far from the barriers. Even came face to face with a certain Emmanuel Karangwa. He was a militiaman neighbor. He said to Mom: “In your family here everyone has been killed. But in Kibagabaga, in the Catholic Church, there are people in your family who are still alive. I learned that for some time there had been no more violence. You shouldn’t have any problems there. ”

In Kibagabaga, Mum had her whole family there. Mom’s brothers lived there, they got married there. So we looked for a way to get there. We ran into a militia leader called Bizimana. He exclaimed, “Ah, you’re still alive! Go ahead, yours are still there. ” In front of the church, we met other militiamen who instead blocked our way. They asked Mom where she was from and told her they wanted to kill her boys, so me and the three-year-old on her back. My little sister Sylvie was five years old. Mom begged their forgiveness. She didn’t have any money with her. She also told them that she was just a simple farmer. I had already been made to sit on the floor, and they wanted my little brother who was on Mum’s back to sit too. Mom and Sylvie would have their lives saved, but we boys had to die.

At that moment, another militiaman pleaded our case, saying that we were sent by Bizimana. So they told us that they would not let us enter the church, but that we could go home. When we got to the current Saint-Ignace school, we crossed Bizimana. This time he brought us back himself and we were able to enter the church, but not inside.

There were not only people inside this little church, but also plenty of other people on the other side. In the houses behind the church there were people who were related to Mom. This is where we joined them. My cousin, who already had a child, pulled me aside and started to cry. She wondered why we came here, because here too there were daily killings. I told him that we had been kicked out of our hiding place, and we were directed here. She asked about my father and I told her that I had not seen him for several days. I was told about our family members killed the day before. A certain Damascene and a cousin called Mukarusanga. Another girl named Kamondo, along with others, killed previously. She would tell me that at any moment, the killers could come and kill others, and indeed, around 4 p.m., there was an attack. I don’t know how the militiamen were informed, but they went to look for about fifteen Tutsis who were hiding with a certain James. They made them stand in front of the church, in the middle of the road. The soldiers arrived with their guns. These soldiers had their position here behind the church. They ordered that more Tutsi be taken out of the church. Killers entered the church and adjacent houses and took out about eighty people, including our mothers, not to mention the very young children who were on their mothers’ backs.

“It was with this kind of club that they killed my mother, in front of my eyes” -Patrick Kadafi

As I watched all this, my cousin vanished, because he was used to these scenes. A cousin, Ntamanga Nsaziyinka, could not be found. I saw that my sister was not in the cohort. I wanted to go find her in one of the houses, take her by the hand and we go. But this time, I ran into another militiaman who had gone to bring more and he grabbed me. They picked up almost everyone from the houses next to the church, but in the church there were still people left. They put us in the middle of the road and said we had to hurry, because we had to get these people to the doctor. A little later, they put us down the road, on the other side of the church, where there were euphorbias. They put us behind these shrubs. They blew their whistles and started cutting up, beheading people with machetes, hitting them with studded clubs. It was with this kind of club that they hit my mother in front of my eyes. The one holding me by the collar and saying ‘this little boy, we’re gonna kill him last’ was distracted when a Mum stood up and tried to run away. He let go of me to go finish him off. I don’t know what instinct told me to get out of this butcher shop … A soldier saw me on the road and asked me why I was coming back. I told him I had been granted forgiveness. He let me go and I got it into my head to go back to Kimironko.

By discussing later with my cousins, including Ntare, I learned that this is how we had killed, one by one, the Tutsi who were in the church. I went to a soldier who was from our religious congregation and where cousins had taken refuge. People had told me that Dad had been hiding with this soldier. But when I arrived, Dad was no longer there. I spent a few days with this soldier. He made his family flee because he heard the Inkotanyi arriving, Kimironko was becoming a zone of fighting with the RPF.

When the soldier left, his domestic workers kicked us out of the house. We spent a few days with other neighbors. Luckily, my little sister Sylvie joined us and I don’t know exactly how she managed the feat of reaching us, but I know that at one point, she saw soldiers and took refuge in people asking to use their toilet, waiting for the military to leave and for her to come out of the toilet.

In the house of the soldier where we were hiding, there was a little cousin who was only four months old. Her aunt, who was with us, was in the 6th year of secondary school. She was taking care of us, but couldn’t get out. I was given the task of fetching some porridge for the baby, as the others were even younger than me. On the way, I come across a militiaman named Tegejo. He told me that sometimes my parents would send him to draw water, and this time it was my turn. He had three jerrycans that he pushed on a wheelbarrow. He was armed with a rifle. I drew water in his presence and we returned to his home, near my home. He put down the jerrycans and ordered me to walk him home. There was a young girl in his house whom he had made his sex slave. The girl’s daddy lived downstairs and was still alive. We went to see this daddy.

When we arrived in the neighborhood called “Mushimire”, we met another militiaman who knew my family. He said to the other militiaman: “But why are you lugging around this cockroach from Sizeri [Patrick’s father] and Kadogo [his father’s little brother had joined the RPF and that’s what they called them young RPF recruits]?” He loaded his rifle and Tegejo loaded his too, refusing to let him kill me. But the other fired a bullet that hit the skin of my cheek. Tegejo wanted to shoot too, but the other militiamen dissuaded him, saying they were like brothers and should not kill each other.

Tegejo took me to Kanombe so that I could receive treatment. Other wounded were being evacuated as the RPF approached. One of the doctors said that even if they could, they would not cure “this Inyenzi”. So we came back. He continued his own activities and released me. It was already evening, I could no longer go get the porridge for the baby. I was also tired and didn’t know if there was any more. Those who lived with me must have thought I had been killed. Where we were, there were seven children. When the Inkotanyi approached, we had hopes that they could come and save us.

Some people told government soldiers that there was a place where Inyenzi were hiding. The military did not want us to stay and demanded that we follow the others. They thought we could be identified and killed at roadblocks. We spent a few days in Giporoso. The refugees came and chased us away. And in the meantime, the child who was on the aunt’s back died. We returned to Bibare and the militiamen took away my aunt, who must have been killed because we never saw her again. They left us alive, saying they would kill us on the day of President Habyarimana’s burial. There was a barrier where we were told that we could have something to eat, because there was a vehicle passing to feed the militia. They agreed to feed us, because on the day we died, they preferred, they said, to see us healthy and plump.

Liliane Umurungi found by the Inkotanyi, when worms had started to devour her

We slept in the entrance of a house. Sometimes a militiaman would pass by and could slap or beat us. After a few days, we ran into a man named Mohamed. He picked us up at his home. He took good care of us. A few days later, the militiamen wondered where we were. They decided to search the houses around. When our protector found out about this, he woke us up at four in the morning. He directed me to a road where there were eucalyptus trees, which led to Giporoso. We entered a mosque which, it seemed, the militiamen could not enter. There were other people. In the evening, they brought us food. And when the RPF captured the airport, we followed the cohort of fugitives. When we arrived in Kicukiro, we saw Mohamed again. We spent the night there. The next day, we continued to walk to Butamwa. There was a lot of firefight, especially as the military was also fleeing. There is a little cousin on the paternal side, Liliane Umurungi (four years old), remained among the bodies, the corpses. Maybe because of she was tired, of hunger, she stayed there. She has been able to survive, in the end. She was found by the Inkotanyi, when the worms had started to devour her. She was in the midst of the rotting corpses. When we saw her, she was silent. She could only speak correctly from the 6th year of primary school. And even now, during commemorations, she relives this nightmarish, traumatized story.

We continued and we arrived in Gitarama prefecture after crossing the Nyabarongo river. I was with Kayitesi (ten years old, Liliane’s big sister), Tintin (seven years old), D’Amour (three years old)… At the place called “Ku Mugina”, we were separated from our protector Mohamed. He tried to defend us by saying that we were his children, and then the militiamen put Tintin next to him, and he sheepishly said the truth, that Mohamed was not his father, and that we had passed him by chance on the road. He also said that his mother was killed by militiamen …

“They were about to hit me with a sledgehammer, but I threw myself in the pit”

So the killers took us to the edge of a pit dug in a banana plantation. They killed the children with clubs by throwing them into the pit. I was the only survivor among these children: they were about to give me a sledgehammer, but I threw myself in the pit. They figured I was going to die in that pit and left. The hole was maybe ten meters deep, but it wasn’t that deep anymore, because a lot of bodies were piled up. They said they were going to get stones to stone me, but it started to rain. I managed to climb the walls because there were little hollows I could hang on to. These little holes were made so that those who were digging could come up. I walked along the road so as not to encounter a barrier, then I arrived in downtown Gitarama.

In Cyakabiri [an area of Gitarama], I was also lucky. I was hungry, I asked a soldier for food. He took me to a health center where wounded soldiers were taken. He asked me to stay there and assured me that he would not hurt me. He showed me where I was going to sleep. He was a soldier, so he went on operations. I stayed with him when he wasn’t working. One day, when I was going to draw water, I met a warrant officer who lived downstairs. He told me that if he saw me in the camp again, he would kill me. In the evening, I told my protector about it. He told me not to worry, that the warrant officer did not own the camp.

Two days later, I ran into the warrant officer who led me to a barrier and said to the militiamen, “See where you can put that cockroach!” . They took me down to a state training center. There was a hole. They told me to step into it. They asked me about my origins. They called me Inyenzi, I told them that I was not one, that I was among the refugees and that I had lost them along the way. However, behind the banana plantation, someone was hiding. He ran out and my tormentors started chasing him. I was able to go back to town.

The Inkotanyi arrived and I started to flee with the others. I tried to avoid people from Kimironko for fear of being recognized. When I arrived in Nyakabanda, on the border with Satinski commune, I saw that those suspected, adults or children, were thrown into the river. We weren’t even looking at their ID cards. They were telling them to show their hands, their ribs, their faces. ,,

So I made the decision to turn back. When I got to a barrier, I pretended to cry. I returned to the Nyabikenke center. It was dark. I sat down. A man came, I asked him to eat. He asked me where I was going to sleep. He took me home, gave me food and I slept soundly until the next day at 10 a.m.

I told them that I was from Kigali, that I was fleeing and that I had lost mine along the way. They offered to take me to the nuns, because maybe I could meet my family there. I had decided to turn back to meet the Inkotanyi there. I finally told them that I had lost mine a long time ago, without telling them that they had been killed by the militia. I told them I preferred to either stay there or turn back. They agreed to let me stay.

After a few days, the Inkotanyi arrived. They told us to go back to our homes and not be afraid. They invited the population to a pacification meeting calling for them to lay down their arms, because peace had returned. When I arrived in Nyabikenke, the killings had stopped, there were no more barriers, nor people to kill. Life resumed its course: the farmers cultivated, and I kept the cows.

After a few days, we learned that Kigali was liberated, then that the government had been put in place. I was always staying with the same family, that of Félicien Munyankindi. The latter had a younger brother named Silas, who was a trader. He came to collect goods in Kigali, then he came back saying that everything was back to normal. So the idea was that next time I would go to Kigali to see.

In August-September, I came back with him. We slept in Kicukiro. The next day he asked me if I still remembered where I lived. It was a Sunday. Arrived at IAMSEA [between Remera and Kimironko], we met a former Hutu classmate, and he said to me: “Gaddafi, you are coming back from your exile!” I was afraid. Were the militiamen still chasing us? He told me that he saw my father sometime. Arrived near my house, I saw Mama Ruseruka, a lady who was praying with my mother. She was very surprised to see me again. She greeted me warmly and asked me to greet her husband Karemera as well. They confirmed to me that my father was still alive and at home. This surprised me a lot, as there were to be no more doors, no windows, and even less stuff inside. When I arrived there were even curtains. I knocked on the door. Dad opened it.

We got together, he lived with my little sister. He went to wake up my little sister to come and say hello, but she preferred to stay in bed! I thanked the people who had accompanied me, including Silas. “

27 years after the Genocide: Creation of a Ministry for National Unity and Civic Engagement

Today in July 2021, the Rwandan Government has created a Ministry for National Unity and Civic Engagement with the objective of always consolidating the Unity of Rwandans and getting them to convince themselves to always fight ideology of the Genocide which spreads violence and divisions. Whether in Rwanda or abroad. This is proving to be a top priority.

Since then, Rwanda has announced the arrest and trial of Genocide criminals. Trials took place, followed by confessions and repentance. About 20 criminals were sentenced to death and executed. Other Genocide detainees have served their sentences and are free. Others are still serving time or life. The country has seen fit to abolish the death penalty. And initiate a policy of reconstruction and national reconciliation. Spectacular progress has been made. The country’s economy has rebuilt itself even though there is still more to be done.

The inhabitants live together by carrying out development work that is useful to all. It is a constant and continuous process that is consolidating. Other post-conflict countries are visiting Rwanda and trying to learn from its model, to rebuild quickly and better.

But other detractors still preach the ideology of exterminating the other in Rwanda or abroad. Various strategies are deployed by all Rwandans to maintain social cohesion, living together and inclusive growth.

After the Tutsi Genocide, the young Patrick Kaddafi grew up in this environment. He completed his secondary and higher education. He is a valuable technician who works on mechanical devices deployed in various road sites, in the process of setting up infrastructure across the country. He believes that with leadership like that in Rwanda, countries can always avoid the worst. What matters now is to work together with other citizens to preserve a future of lasting peace and security, viable for all. That vigilance concerns everyone, because the evils of violence slumber and can wake up at any time and repeat the worst. But the hope is to always fight and overcome the evil. This is the mission of the entire Rwanda and the whole humanity. (End)