Nyabarongo river, water looking muddy brown due to pollution and poor agricultural activities in Western Rwanda

By Aimable Twahirwa;

Kigali: It is a hot Monday morning in Nyamagabe, a mountainous district in the Southern Rwanda, a group of young men and women gather for a meeting to share key lessons on hands-on practices to contain soil frequently washed away into neighboring Nyabarongo river due to erosion.

The initiative is part of a community engagement toward national efforts to protect Nyabarongo river catchments targeting 1.9 million contracted farmers to sustain benefits it brings to the local population by applying terraces, agro-forestry and afforestation along the banks of this river which is part of the upper headwaters of the Nile.

“Through the project, we learnt a lot of improved farming techniques using various conservation practices,” says Alphonsine Mukangarambe, head of “Abishyizehamwe” a local cooperative for young farmers.

Abishyizehamwe, which means ‘those who come together,’ was formed in 2015 to mobilize local community in Nyamagabe district on retaining soil and water which is carried away along Nyabarongo river.

Radical terrace cultivation

As of August 2019, about 138,452 hectares of upper Nyabarongo river catchment area have been maintained by landowners, according to official estimates

During the implementation phase, the project is targeting youth in various economic activities such as farming from some selected districts including Muhanga (Central South), Ngororero (West), Ruhango (South), Nyamagabe (South) Gakenke (North) to protect Nyabarongo watershed by reducing soil erosion, protect and enhance water quality.

The Upper Nyabarongo catchment is part of the Nile basin and runs from south to north in the western parts of Rwanda over an area of 3,348 km².

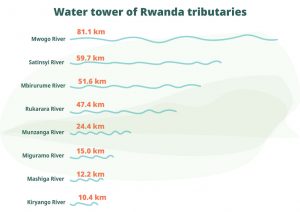

The catchment is known as the water tower of Rwanda and boosts a significant number of tributaries, of which the most important are (from south to north) the Mwogo River (81.1 km), Rukarara River (47.4 km, springing from the Rubyiro and the Nyarubugoyi rivers), Mbirurume River (51.6 km), Mashiga River (12.2 km), Kiryango River (10.4 km), Munzanga River (24.4 km), Miguramo River (15.0 km) and the Satinsyi River (59.7 km).

The catchment is known as the water tower of Rwanda and boosts a significant number of tributaries, of which the most important are (from south to north) the Mwogo River (81.1 km), Rukarara River (47.4 km, springing from the Rubyiro and the Nyarubugoyi rivers), Mbirurume River (51.6 km), Mashiga River (12.2 km), Kiryango River (10.4 km), Munzanga River (24.4 km), Miguramo River (15.0 km) and the Satinsyi River (59.7 km).

Currently, all members of the community with land on Nyabarongo river catchment have been registered to be supported and collaborate in the project’s implementation, with Rwandan officials placing special emphasis on using Nile waters as the country pleases.

While the initiative focuses attention on the rural youth and young farmers, this category of labor force is encouraged to take advantages of terrace farming as a move to reduce soil loss due to water erosion.

Under different projects to protect the river, some 912 hectares of 1,102 that occupy Nyabarongo catchments, have been rehabilitated so far in Muhanga (Central) and Ngororero (West) districts by applying terraces, agro-forestry and afforestation as well as promoting sustainable mining, according to official reports.Thanks to this initiative, a number of young farmers in Nyamagabe have been able to grow major productive crops including cassava, potatoes, sweet potatoes, maize and beans.

Now Mukangarambe says these efforts have necessitated changes in how young farmers cultivate their land on steep slopes to prevent erosion and be able to provide food and secure incomes in a sustainable manner along Nyabarongo river.

The head of Integrated Rain Water Management at the Rwanda Natural Resources Authority, Francois Xavier Tetero explained that by making concrete catchment plans involving youth among local farming community, Rwanda’s water resources can be utilised efficiently and effectively.

However, Mukangarambe laments that young farmers from these remote regions are not given adequate opportunities to participate in the implementation of such initiatives

“Young farmers are affected more than anybody else but when such initiatives are promoted, you find very few young people from these areas involved,” she said.

Challenging the hegemony in the Nile river basin

Nyabarongo river catchment project was introduced in 2010 after Rwanda ratified the Nile Basin Co-operative Framework Agreement to ensure enough water for agricultural irrigation projects, water processing industries and suppliers, hydropower projects and other projects that need water use permits.

This law ratified in 2010 allows individual countries to use shared resources for their own development, it also requires that any new development does not cause harm to another country, according to experts.

Running through eleven countries for 6,853 kilometres, the Nile is a lifeline for nearly half a billion people.

All the cities that run along the river exist only because of these waters. For Egypt, this is particularly true: if the Nile wasn’t there, it would be just another part of the Sahara Desert.

Egypt has tried to be master of the river for centuries, seeking to ensure exclusive control over its use. Nevertheless, today upstream countries including Rwanda are challenging this dominance, pushing for a greater share of the waters within upstream river catchment.

Egypt and Sudan still regard two treaties from 1929 and 1959 as technically binding, while African upstream nations – after gaining independence – started to challenge the agreements signed under colonial rule.

The 1959 treaty allocates 75 percent of the river’s waters to Egypt, leaving the remainder to Sudan.

Egypt has always justified this hegemonic position on the basis of geographic motivations and economic development, as it is an arid country that could not survive without the Nile’s waters, while upstream countries receive enough rainfall to develop pluvial agriculture without resorting to irrigation.

The Nile Basin Initiative (NBI), created in 1999 with the aim to “take care of and jointly use the shared Nile Basin water and related resources”, could be an example of regional multilateralism to resolve disputes but it remains relegated to discussions about water management.

Institutionally, the NBI is not a commission. It is “in transition”, awaiting an agreement on Nile water usage, so it has no legal standing beyond its headquarters agreement with Uganda, where the secretariat is settled.

Due to differences that have not yet been resolved, the NBI has focused on technical, relatively apolitical projects. This ends up weakening the organisation since Egypt sees technical and political tracks as inseparable. Therefore, Cairo suspended its participation in most of NBI activities, effectively depleting the organisation’s political weight.

Capacity development

Rwandan officials believe that Nyabarongo watershed protection creates another mechanism for practices with the objective to raise the capacity for better water management and good practices of the Integrated Water Resource Management in the country.

“We hope that by 2024, these joint efforts from all stakeholders including youth would help turn again Nyabarongo river into clean water,” observes said.

In a recent interview with reporters in Kigali, Ebel Smidt, Team Leader at Water for Growth Rwanda explained that Upper Nyabarongo catchment was the first project on landscape restoration and protection of the hydro power plant introduced in Rwanda.

“We are trying to develop capacity and ability of various stakeholders in water management along the upper headwaters of the Nile,” said Smidt.

The project jointly funded by the Government of Rwanda and stakeholders, is currently focusing on all surface water emanating from rainfall-runoff within these boundaries and that runs downhill towards the shared outlet.

Now, local administrative officials sees the potential of involving youth in the protection of natural resources as a cost-effective approach to ensuring a supply of potable water.

In watershed protection programs such as those on Nyabarongo river, young farmers are paid to use soil and water conservation techniques – payment that benefits the community, said Jean Lambert Kabayiza, the Vice Mayor in charge of Socio-Economic Affairs in Nyamagabe district.

This article was published with financial support of InfoNile and the CIVICUS Goalkeepers Youth Action Accelerator.